Do not be afraid! God keeps his promises.

I wrote these reflections on how to live free from fear and anxiety, how to be a people of hope, before last week’s decision concerning assisted suicide.1 In light of that vote, however, these ideas are particularly important.

One of the famous texts that is read at 9 Lessons and Carols most years is Jeremiah 33:14-16. It is all about hope and fear.

Jeremiah begins his message to Israel with reassurance about God’s faithfulness:

The days are coming,’ declares the LORD, ‘when I will fulfil the good promise I made to the people of Israel and Judah.

It is worth sitting with this for a moment. God makes promises to us. He is a promise making God.

Incidentally, God doesn’t have to be like this. He could be arbitrary – doing whatever he wants whenever he wants it. That kind of God is a tyrant, untrustworthy and unreliable. We intuitively know God isn’t like this. It is written into the very fabric of the universe which, completely unnecessarily, is governed by laws. In that it reflects the character and mind of its Creator.

One of the earliest things we read God say in Scripture is a promise. We can read about this in Genesis 3:14-15.

Through Eve and then Adam sin had entered the world. She had received a message from an angelic messenger – pictured here as a serpent – who tempted her with a promise of power. If only she defied God, humanity would take God’s place. And so she had taken the fruit and ate. It was an act of defiance, of rejection, and it brought a poison into humanity that would eat up and kill generation after generation. They would be cut off from the presence of God and his light. This is always the path when we choose darkness. Man and woman are promised that they will become like God; instead they become less than human. The rejection of light and life is the embrace of darkness and death.

But at the outset of this creeping darkness God spoke a promise of light. One day there would arise a woman who would have a Son and that Son would crush the serpent. He would provide a Redeemer to deliver humanity from the curse it had brought upon itself. These promises are repeated in different forms throughout the Scriptures to Israel and then to her kings and prophets. King David is promised a son who would reign not as one who dies but who lives forever.

We can read these promises, and receive them for ourselves. Perhaps you feel you have had promises from God – that you would flourish, that your friend or family member would come to know Jesus, that he would never forsake you. But at times it feels as if the promise is failing. We wait and wait but still the darkness advances and we come to fear the future, to fear the power of the Serpent, to fear that God has failed.

That was the position of ancient Israel when Jeremiah spoke. The promise to King David seemed in ruins. The kingdom he built had divided, his sons had failed morally, politically, militarily. And his people were going into exile. On and on the darkness marched as the Serpent’s voice seemed the only one that sounded.

It was precisely at this time that Jeremiah reaffirms the promise. He calls his people to hope.

God speaks in the midst of the darkness and what he says is “Fear Not!” “Do not be afraid”. The God of Israel, of the Cosmos, of your heart, is the God who lives and reigns even when darkness abounds.

The hope of Israel may seem to have fallen and been crushed but God is going to make it spring up, sprout from the broken stump of David’s line. Can you feel the imagery? David’s tree has been axed down, felled and broken. But in this moment of death God is going to bring resurrection.

And so we come to Luke 1 and the story of the annunciation. The familiarity of the verses can blind our eyes to the reality of what is happening.

Here is the second woman, filled with grace (v.28). Your copy will read “highly favoured”, literally, saturated with God’s gifts. She is one who has been prepared and sanctified by God for this moment. While Eve’s sin had separated humanity from God and now to Mary comes the word: “God is with you”. Eve had brought the Serpent to power; through Mary will come the One to crush that Serpent’s head. And where Eve had defied God’s design for her grasping power and equality with God, Mary would reply “I am the Lord’s servant…May your word to me be fulfilled.” To the woman comes an angelic message. The promise is to be fulfilled. David will have his king to sit on the throne.

Suddenly, when hope seemed lost, when Israel was dominated by tyrants, humiliated and oppressed, when the promises of God were a long-held but distant memory, God acted. He had been working through all the ages even when we could not see it.

He was working in Cain and Abel, in the flood of Noah, in Abraham and Joseph, in David and Solomon, in Ruth and Moab, in Esther in Exile, through Isaiah and Jeremiah and Micah and the Macabees. It was hard to see, darkness seemed to reign, death seemed ever more present. Fear was a natural response. And yet God was working.

And so he brought a new Eve, ready to bear the fulfilment of every promise – the eternal yes, the final word: Fear Not!

Even as Christ battled demons, diseases and demagogues, darkness and death seemed to triumph. But a voice would echo from the despair of Calvary: Fear Not! And Christ would rise triumphant from the grave.

My friends and fellow-sinners. I don’t know what promises you have received from God this year or through your life. Some of us are in that moment of rejoicing, standing with St Mary and acclaiming with joy: How can this be? What a God who fulfils his promises!

Some of us are in exile with Jeremiah, looking at a life which seems marked with pain where the presence of evil is all too obvious. The temptation is to despair, to succumb to fear of the present of the future. If that is you, you are in good company. But my message to you this morning is the same as Jeremiah’s: Fear Not!

The God of Israel, the God of Eve and Mary, the God of Jesus Christ has not forsaken you or forgotten you. It is precisely from the place of death that we encounter resurrection power.

The world can seem increasingly dark. There are wars and rumours of wars. The gospel retreats in the West even as it advances in the East and in Africa. At times it feels as if the Serpent is winning and the kingdom of death and darkness are at hand. But even now, especially now, God is at work. He has not forsaken us. He will not forsake us. Fear Not!

There will be a day when you will stand in glory with Mary and acclaim the glorious faithfulness of her Son. When you will stand with Jeremiah and say: I saw the fulfilment of the promises. When the hand that flung the stars and surrendered to nails will wipe the tears from your eyes and speak over you words of love and grace. Fear Not!

If your life is hard, then take heart. God hasn’t forsaken you. Lean into him. Find a good prayer app or practice that you can hold onto even when life is hard. You can try the Bible in One Year, Lectio 365, or Hallow.

Often the answer to our prayers, the fulfilment of God’s promises in our lives, requires our consent, our courage. Mary is our mother in this: we need to resist the temptation to become hardened or so sad that we are unable to say ‘yes’ when the promises begin to be fulfilled.

Finally, we need the courage to live as men and women of hope and life in the midst of a culture that embraces despair and death.

Our culture is becoming increasingly dark. This is likely to continue. Once one has accepted the logic that unborn life can be terminated for reasons of convenience or, to be blunt, finance, the logic of terminating other inconvenient life becomes irresistible. And so it has proved. This is a deeply dangerous trajectory for a society to be on and it can cause us to feel lost and afraid.

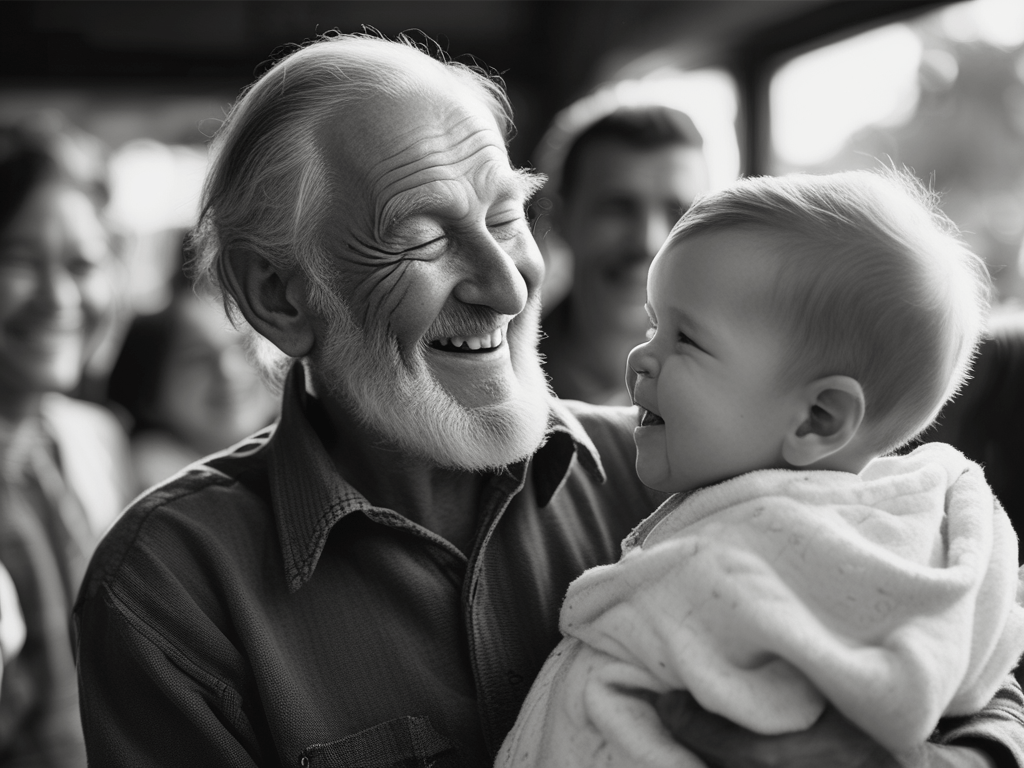

The alternative is to have the courage to keep on choosing Christ, to keep on choosing life. We can be committed to embracing new life in babies, to making our homes, families, workplaces, friendships as open to life and grace as we can. We can embrace the stranger, care for our elderly, show love and compassion to our enemies. We can resolve never to give in to nihilism or self-centredness and instead keep living for the sake of God and of others. This will not be easy. But it is possible because God keeps his promises.

- I refuse to use the euphemism ‘assisted dying’: words matter and we should not hide from the reality that what was approved last week is physicians giving poisons to patients so that they can kill themselves ↩︎